Bottles Against COVID-19

Lacking a summer job thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, my sister and I wanted to make the most of this situation by helping those around us. So, we created BottlesAgainstCOVID.org. This not only made it easy for us to collect empty bottles from our neighbours, but easy for anyone else to sign up and do the same. The intent is for all proceeds to be donated to charity. In our case, we raised over $3k for St. Joe's Hospital in Toronto.

How it all started

During the COVID-19 pandemic people have been spending a lot more time at home. With this, alcohol consumption has increased greatly. In the USA, some studies suggest a 55% year-over-year increase in alcohol sales from this time last year. Surveys show that Canada is no different. While this "coping mechanism" is ill-advised by the WHO, it seems that people do not seem to care all that much.

It was my sister's idea to turn this into something positive. She figured that all the empty bottles sitting at people's homes could be returned to the Beer Store, and the proceeds could be donated to charity. Her charity of choice was the St. Joe's Hospital COVID-19 fund. She created a calendly page and posted on a few local Facebook pages. Pickup would be completely contactless – registrants would simply leave their empties on their front porch or curb. News of the initiative spread fast, and hundreds of people signed up.

On the first pickup day we realized there was a problem. We had a lot more support than expected. So much so it was overwhelming. Bottle pickup, which was estimated to take 3 hours, took 8. In one day, we collected more than 4000 bottles from over 50 houses. While it was great to see the community rally behind our cause, this amount was overwhelming. It took 6 full days of bottle sorting and returning to get through this amount. The day after we finished was another scheduled pickup day. We needed a way to limit our intake without limiting our impact.

So, I started working on a website. The goal was to create something that could limit the amount of collections by number of bottles (instead of number of pickups) and allow others to join in on our solution. By allowing anyone to create their own bottle drive, we reduce the overall number of people leaving their homes to return empties and empower others to help.

How the website works

The front end is client rendered and communicates directly with the Flask back end using the fetch API. Some pages (home page, FAQ page) are hand-written in HTML with a little bit of JS. Yarn handles package management for the front end.

The Flask back end is mostly RESTful, with one caveat: the server handles session management using the "session" library built into Flask. The back end communicates with the database via the mongoengine library. Poetry handles back end package management.

The database in use is MongoDB. Before this project, I had no experience with MongoDB. Everything I know, I learned from building this website. The decision to chose MongoDB came as a recommendation from a friend to give NoSQL a try.

Searching for existing bottle drives

Searching for drives is likely the most used feature of the website. As such, it is important the search feature be accurate and intuitive. Therefore, the search function is on the main web page, and a user can use either geolocation or a postal code to query for drives in their area.

Clicking the "Search by location" button calls the locationSearch() function. This first checks for the presence of the HTML geolocation API, preventing null errors if the feature is unsupported.

function locationSearch() {

if (navigator.geolocation) {

/*important parts of function go here*/

}

}

Next, it calls this API, triggering a prompt for the user to allow access to their location.

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(/*callback function*/)

The callback function here formats the longitude and latitude results into a URL query string and redirects the user to the search results page.

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(result => {

const queryString = `lat=${result.coords.latitude}&long=${result.coords.longitude}&postal=false`

window.location.assign(`/search?${queryString}`)

})

The "Search by location" button becomes disabled if at any point the function fails to return an appropriate geolocation. Often this occurs when the user chooses to block the website from accessing their precise location. Disabling the button prevents future ineffective search attempts and makes it clear that the user should instead search via postal code.

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(result => {

/*query string and redirect part from above*/

}, error => document.getElementById("locSearch").disabled = true)

Putting this all together (and compacting some of the code), results in the function's final form:

function locationSearch() {

if (navigator.geolocation) {

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(result => window.location.assign(`/search?lat=${result.coords.latitude}&long=${result.coords.longitude}&postal=false`), (error) => document.getElementById("locSearch").disabled = true)

}

}

Postal code searches are first vetted through an input regex statement. This restricts the valid input to that of any 6-digit Canadian postal code with or without a separating space. This statement (taken from here) is quite strict and goes beyond just number/letter alternating pattern. Most interestingly, it follows the Canada Post regulations of not containing letters which can be confused for numbers (I, O, Q, Z, ...).

<input

id="postalCode"

placeholder="K1A 0A9"

pattern="^([ABCEGHJ-NPRSTVXY]|[abceghj-nprstvxy])[0-9]([ABCEGHJ-NPRSTV-Z]|[abceghj-nprstv-z]) ?[0-9]([ABCEGHJ-NPRSTV-Z]|[abceghj-nprstv-z])[0-9]$"

>

After pressing the search button, the postalSearch() function validates the input and queries a public database for postal code information. Also, disabling the search button and changing the cursor prevents repeated queries to the database while waiting for a response. The value.replace(' ', '') line removes the (optional) space between the two parts of a postal code.

function postalSearch() {

const postalCode = document.getElementById("postalCode")

if (postalCode.checkValidity() && postalCode.value !== "") {

document.getElementById("postalButton").disabled = true

document.getElementById("postalButton").style.cursor = "wait"

fetch("https://geocoder.ca/?json=1&getpolygon=1&postal=" + postalCode.value.replace(' ', ''))

.then(result => result.json())

}

}

The geocoder API returns a polygon representing the area covered by the postal code. The function takes this polygon and generates a URL query string. The query includes a Boolean signifying that the search used a postal code. Finally, the function redirects the user to their requested search results.

The final function looks like this:

function postalSearch() {

const postalCode = document.getElementById("postalCode")

if (postalCode.checkValidity() && postalCode.value !== "") {

document.getElementById("postalButton").disabled = true

document.getElementById("postalButton").style.cursor = "wait"

fetch("https://geocoder.ca/?json=1&getpolygon=1&postal=" + postalCode.value.replace(' ', ''))

.then(result => result.json())

.then(value => {

document.getElementById("postalButton").disabled = false

document.getElementById("postalButton").style.cursor = "auto"

window.location.assign(`/search?poly=${value.boundary}&postal=true`)

})

}

}

Upon loading the LocationSearch page, the React component fetches database results by passing the query to the underlying API. State then updates to store the response.

export default class LocationSearch extends React.Component {

/*...*/

componentDidMount() {

fetch(`/api/search${this.props.location.search}`)

.then(result => result.json())

.then(response => this.setState({ response: response }))

.catch(error => console.log(error))

}

/*...*/

}

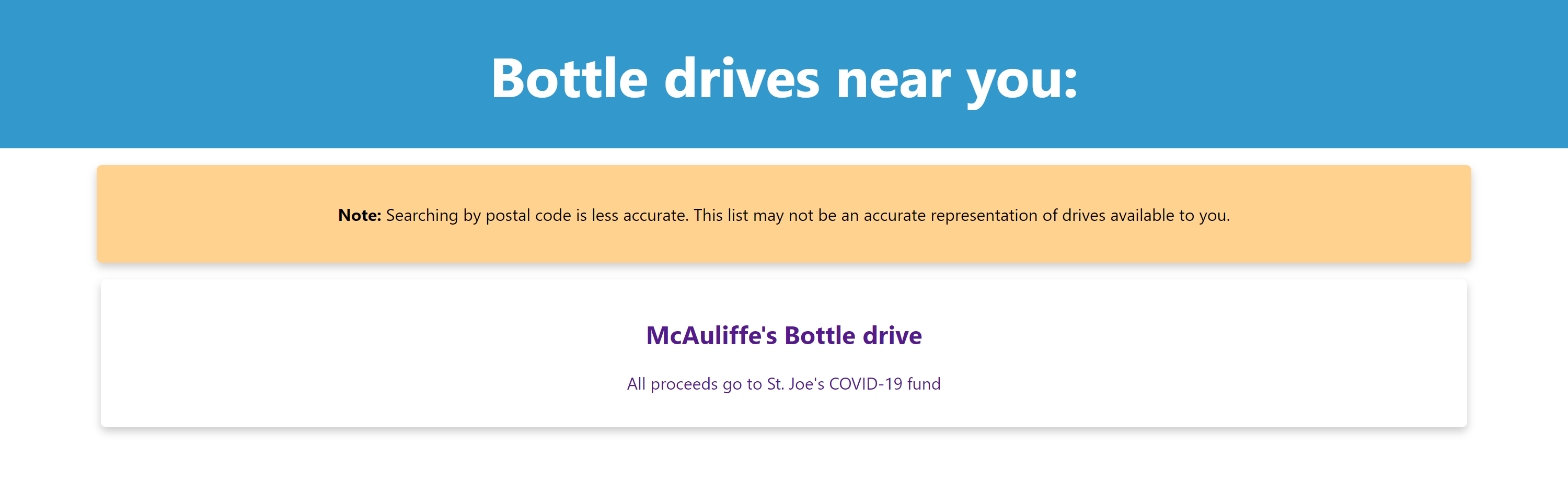

Under the hood, the API parses the query string. The code converts the postal code polygon coordinates into a GeoJSON polygon when required. Of note here is that GeoJSON requires coordinates to be in [long, lat] format instead of the provided [lat, long]. Next, the built-in geo search capabilities of MongoDB become useful. The program queries the MongoDB database for existing bottle drive polygons which intersect with the searcher's GPS location or postal code area. Bottle drive operators define their pickup polygon when they create an account. The web page will show multiple listings if multiple drives are in the searcher's area.

Also, for drives to show up in the search results, the bottle drive operator must have initialized a drive. Bottle drives with no drives will not show up. However, bottle drives with no active drives will appear. This means a bottle drive operator is working in the area, but nothing is available just yet. Drive deactivation occurs automatically when at capacity or if the date of said drive has passed. Perhaps there will be new drives in the future, so the searcher can view the page to bookmark/share accordingly.

class SearchForDrivesApi(Resource):

def get(self):

try:

loc = None

if request.args.get("postal") == "true":

polyResult = request.args.get("poly").split(",")

loc = {

"type":"Polygon",

"coordinates": [[]],

}

for i in range(0,len(polyResult)-1,2):

loc["coordinates"][0].append([float(polyResult[i+1]),float(polyResult[i])])

loc["coordinates"][0].append(loc["coordinates"][0][0]) # GeoJSON polygons must end with their starting coordinate

else:

loc = [float(request.args.get("long")) , float(request.args.get("lat"))]

drives = User.objects(geo_region__geo_intersects=loc, drives__not__size=0)

driveList = []

for i in drives or [None]:

driveList.append({

"name":i["name"],

"link_code":i["link_code"],

"header":i["header"],

})

return(jsonify(driveList))

except Exception as e:

raise InternalServerError

Handling bottle drive sign-ups

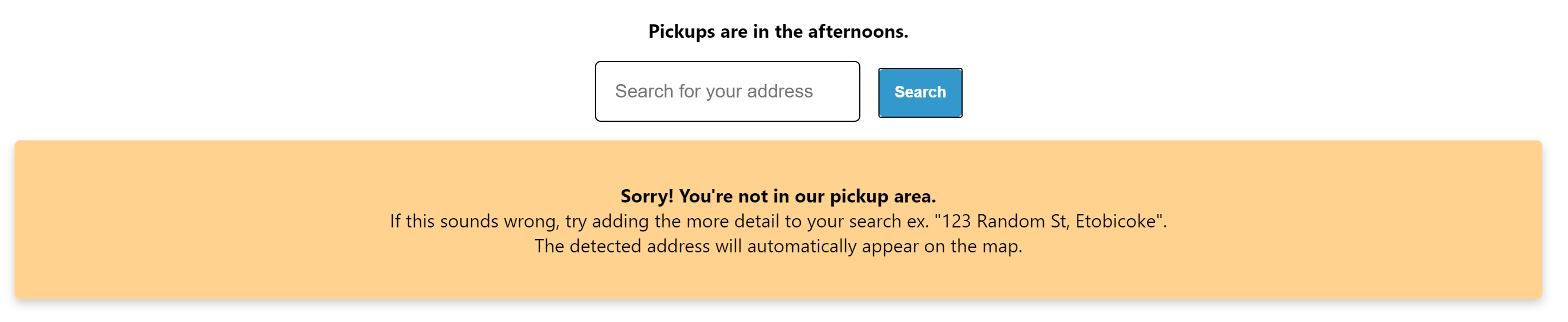

The website redirects the searcher to the individual drive page upon clicking through on the search result card.

Here the user will see the drive pickup area, the time of day bottle pickup occurs, and the charity specified by the bottle drive operator. With the address search feature, they can begin the process of signing up for a bottle pickup.

All this data comes from a get request with the 5-character link code matching that of the current web page (ex. bottlesagainstcovid.org/XXf3d has a link code of XXf3d).

componentDidMount() {

fetch("/api/" + this.state.link_code)

.then(response => {

if (response.status === 200) {

return response.json()

} else if (response.status === 404) {

window.location.replace("/404")

}

})

/*...*/

}

On the server side, Flask uses the 5-character link_code in conjunction with the current date to query the MongoDB database for drives the operator is running.

def get(self, link_code):

try:

pickupInfo = PickupInfo.objects(link_code__exact=link_code, date__gte=datetime.now()).order_by('date')

# ...

Each drive object has a created_by field which links to a user object. The user object stores info on the bottle drive operator. The response requires the operator's name, their pickup region polygon, their preferred pickup times (morning/afternoon/evening), and their header message, which will display the charity they intend to donate funds to.

def get(self, link_code):

try:

# ...

userInfo = User.objects.get(id=pickupInfo[0].created_by.id)

pickupObj = {

"drive_name":userInfo.name,

"pickup_times": userInfo.pickup_times,

"dates_and_crates_left": [],

"geo_region": userInfo.geo_region,

"header":userInfo.header

}

# ...

Next, the code iterates through all the active drives returned as pickupInfo. This loop appends a tuple with the date of each active drive and the capacity of bottles they have remaining at the time of the query (limit - current amount) to the dates_and_crates_left key of the pickupObj. The final step is returning pickupObj.

def get(self, link_code):

try:

pickupInfo = PickupInfo.objects(link_code__exact=link_code, date__gte=datetime.now()).order_by('date')

userInfo = User.objects.get(id=pickupInfo[0].created_by.id)

pickupObj = {

"drive_name":userInfo.name,

"pickup_times": userInfo.pickup_times,

"dates_and_crates_left": [],

"geo_region": userInfo.geo_region,

"header":userInfo.header

}

for i in pickupInfo or [None]:

if i.active == True:

pickupObj["dates_and_crates_left"].append((i["date"].strftime("%Y-%m-%d"), i.crates_limit-i["crates"]))

return jsonify(pickupObj)

# ...

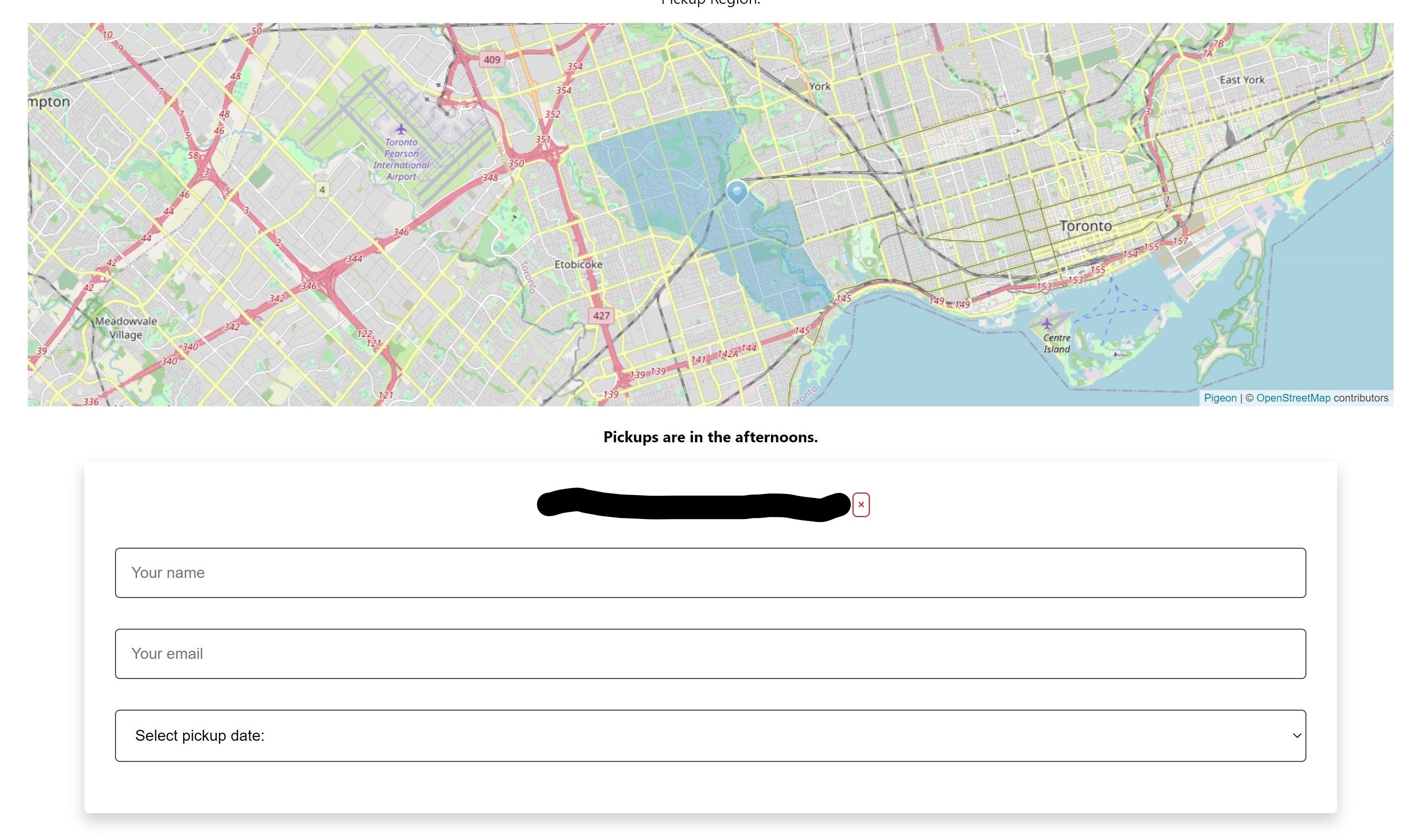

Before signing up, the user sees the pickup region as an SVG drawn onto the map. This feature uses the latLngToPixel() function provided as a part of the pigeon-maps library. Using a dynamic map with an SVG instead of a static image is advantageous because it allows user interaction (panning & zooming).

This function maps each geo-coordinate in the geoJSON polygon to a corresponding pixel on the map.

function Polygon({ mapState: { width, height }, latLngToPixel, coordsArray, colour }) {

let coords = ""

for (let i = 0; i < coordsArray.length; i++) {

let latLngPixels = latLngToPixel([coordsArray[i][1], coordsArray[i][0]])

coords += `${latLngPixels[0]},${latLngPixels[1]} `

}

return (

<svg width={width} height={height} style={{ fill: colour, opacity: 0.4, top: 0, left: 0 }}>

<polygon points={coords} />

</svg>

)

}

A library called polylabel determines the center point of this map. This library aims to find the "visual" centre of the polygon and avoids issues caused by irregular shapes. Usage is as simple as passing the entire geoJSON coordinate array as a parameter. The result is a 2-element array.

let center = polylabel(result.geo_region.coordinates)

To sign up for a bottle drive, the user first searches for their address. Nominatim matches this query with the Open Street Map (OSM) address database.

This "search address first" method allows for verification that the address is eligible for pickup. The robust-point-in-polygon library means we can check that the geo-coordinates of the searched address fall inside the pickup region. This method also ensures no errors in street name spellings that could make pickup difficult.

The website blocks users from completing further sign-up steps if they are not within the specified region.

The searched address also appears on the pickup region map so the user can visually see if the address is correct and whether they fall inside the pickup region. The first few form fields also appear.

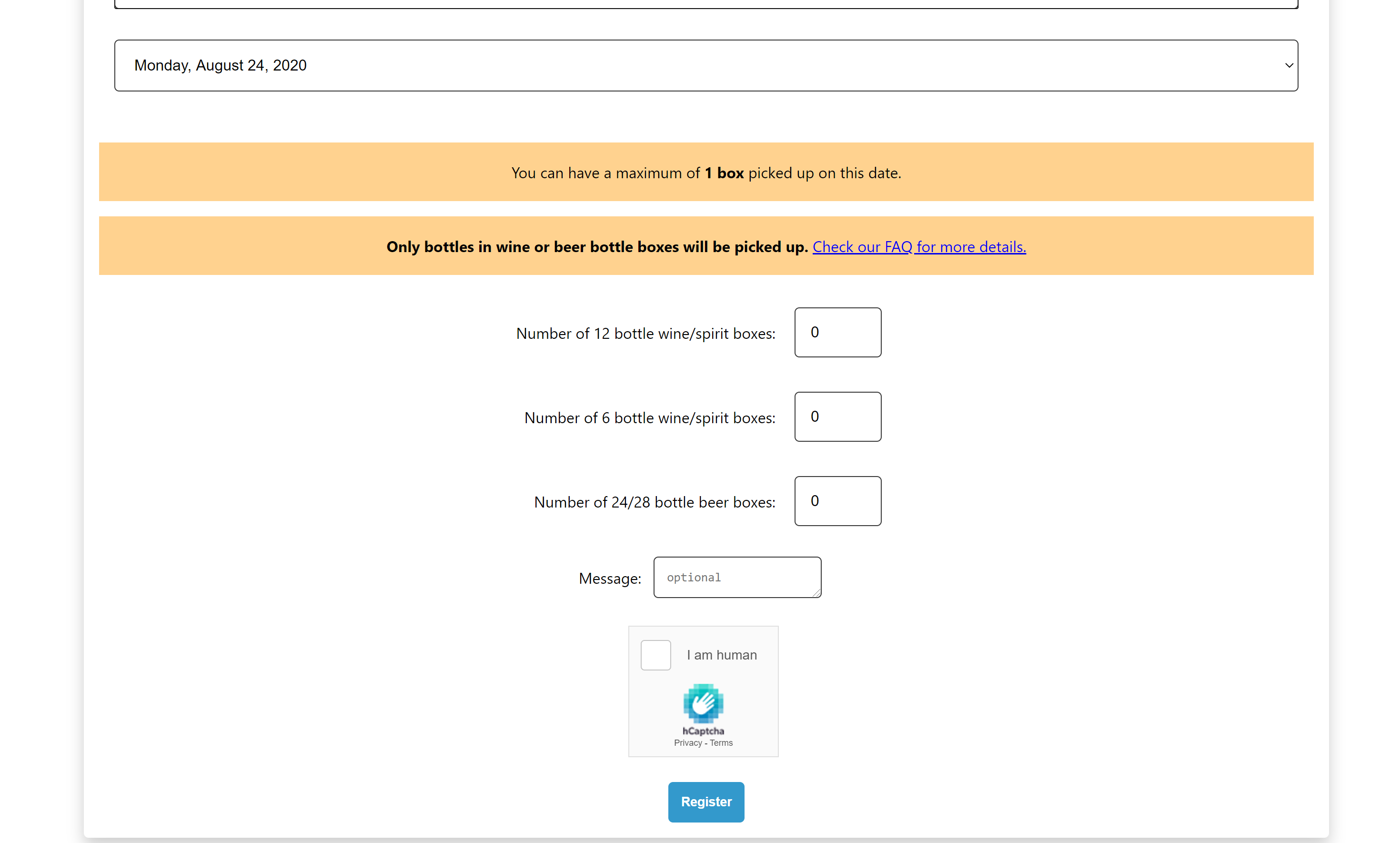

After selecting a date, the rest of the form fields appear.

Here the user can note how many boxes of bottles they would like to donate. Individually, these fields must be greater than or equal to zero. Together, their sum must be less than the limit. The front end only sends the sum back to the server. Separating the fields encourages users to follow the restrictions for pickups (ex. no cans).

Using hCaptcha blocks any possibility of bots filling out the form. It also provides the opportunity to pay back Wikimedia who works with OSM to provide map services for free. All funds generated from using hCaptcha are automatically donated to Wikimedia. Successful completion of the hCaptcha field stores a token in state.

The state object stores each field of the form as it is being filled out. Submitting the form calls the onSubmit() method.

onSubmit(event) {

if (this.state.disabled === true) {

/*...*/

} else if (this.validateInput() === true) {

let myHeaders = new Headers();

myHeaders.append("Content-Type", "application/json");

const signupData = {

"details": {

"name": this.state.name,

"homeAddress": this.state.address,

"neighbourhood": this.state.neighbourhood,

"email": this.state.email,

"crates": parseInt(this.state.twelvePack) + parseInt(this.state.sixPack) + parseInt(this.state.beerBottles),

"message": this.state.message,

},

"date": this.state.dates_and_crates_left[this.state.selectedDate.split(',')[1]][0],

"token": this.state.hCaptcha_token

}

const requestOptions = {

method: 'POST',

headers: myHeaders,

body: JSON.stringify(signupData),

redirect: 'follow',

};

fetch(`/api/${this.state.link_code}`, requestOptions)

/*...*/

}

}

Assuming valid input, the code first constructs the signupData object. This object uses info stored in state. Next, the program sends a post request to the /api/{link_code} endpoint. This is the same URL which the drive info was fetched from in the componentDidMount() method.

Server-side, the first operation is parsing the json into a python dictionary.

class SignupApi(Resource):

# ... get request code shown earlier ...

def post(self, link_code):

try:

body = request.get_json()

# ...

Authentication of the hCaptcha token must happen server-side for proper protection against bots. Client-side captcha authentication can be overridden, defeating its sole purpose. Here the back end redirects the token sent by the client to hCaptcha's servers. The requests library handles this. The request returns { success: True } for valid tokens and { success: False } for everything else (expired or invalid). In the case of an invalid token, the server throws an InvalidTokenError, breaking the try-except block.

class SignupApi(Resource):

# ...

def post(self, link_code):

try:

# ...

token = body.get("token")

data = { 'secret': current_app.config["HCAPTCHA_SECRET_KEY"], 'response': token }

response = requests.post(url="https://hcaptcha.com/siteverify", data=data)

if response.json()["success"] == False :

raise InvalidTokenError

# ...

except InvalidTokenError:

raise InvalidTokenError

# ...

The next step is querying the MongoDB database to access the object representing the requested bottle drive. This means the link_code and date match that sent in the post request.

class SignupApi(Resource):

# ...

def post(self, link_code):

try:

# ...

pickupInfo = PickupInfo.objects.get(link_code__exact=link_code, date__exact=body["date"], active=True)

#must query to determine uniqueness as it is required on a per-date basis

if pickupInfo.addresses.filter(homeAddress=body.get("details").get("homeAddress")).count() > 0:

raise NotUniqueError

pickupAddresses = PickupAddresses(**body.get("details"))

pickupInfo.update(push__addresses=pickupAddresses, inc__crates=body.get("details").get("crates"))

# ...

On line 8 the code checks to make sure the user has not already registered for a pickup on this date. This prevents someone from accidentally filling up the capacity of a certain date when they only intended to edit their previous sign up info. Unfortunately, an edit system is not implemented. The user can save their extra bottles and sign up for the next pickup date. Most, however, just put their extra boxes out anyway. We still picked them up.

After passing all these validation checks, the details key of body unwraps into a PickupAddresses object. The program stores this object in the database. Using push__addresses and inc__crates avoids a race condition. A race condition (or race hazard) is the name for when a computer tries to do two things at the same time. For example, if two users try to sign up for the same bottle drive at the same time. With some exceptions, computers can only work on one thing at a time. Without proper handling, the computer may store the first address in the database and then immediately overwrite it with the second address. This would mean a loss of data. The first user, despite signing up properly, will not have their information recorded and thus will not have their bottles picked up. Pushing and incrementing prevents this by simply telling the computer to add information to the database instead of specifying where in the database to add information.

Finally, the program compares the number of signed up crates to the designated limit. Reaching the limit automatically switches the drive's active field to False preventing further sign ups.

class SignupApi(Resource):

# ...

def post(self, link_code):

try:

# ...

#check if the max number of crates has been reached

pickupInfo = PickupInfo.objects(id=pickupInfo.id).no_cache()

if(pickupInfo[0].crates>=pickupInfo[0].crates_limit):

pickupInfo.update(active=False)

return True

Handling new bottle drive operators

A key feature of BottlesAgainstCOVID.org is the ability for others to easily create their own bottle drives. While it would be much easier to program just the "regular" sign up, opening the service up to others allows more communities to get involved in the fight against COVID-19.

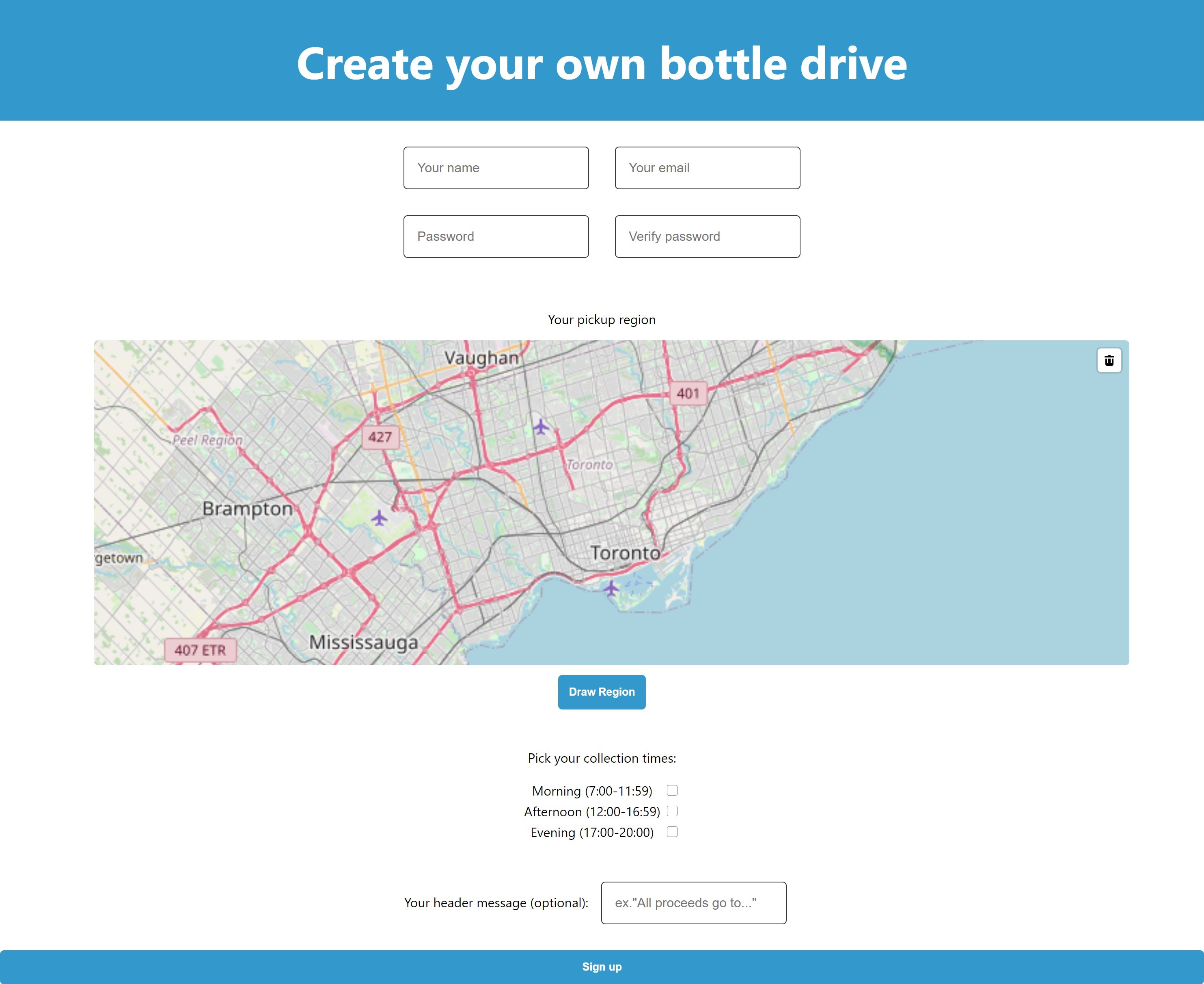

New bottle drive operators sign up at bottlesagainstcovid.org/signup. Here operators complete the usual fields (name, email, password) as well as draw a pickup region on the map.

The text fields work similarly to those on the regular sign up page; the state object stores field data and updates with each edit using the handleInputChange() method. A special case here is when the input is a checkbox instead of a text field.

export default class Register extends React.Component {

/*...*/

handleInputChange(event) {

const target = event.target;

let value;

if (target.type === 'checkbox') {

value = target.checked;

} else {

value = target.value;

}

const name = target.name;

this.setState({

[name]: value

});

}

/*...*/

render(){

return (

/*...*/

<input className="pickup-signup-input" name="name" type="text" placeholder="Your name" value={this.state.name} onChange={this.handleInputChange} required />

/*...*/

)

}

/*...*/

}

The most complex feature on this page is the pickup region drawing apparatus. Here it is in action:

The @urbica/react-map-gl-draw library does nearly all the heavy lifting here. Everything works so long as configuration of the <MapGL> and <Draw> components match the examples on the library's website. Notably the "draw region" control is external. This is because, despite being able to draw multiple polygons, the library only returns the state of the most recently drawn one. To solve this issue, the sign-up page restricts an operator's ability to draw multiple polygons.

The most significant difficulty with this library was the implementation of 3rd party map tiling services. MapBox builds <MapGL> and closely links it to their services. Their free tier requires an API key and thus an account to use. OSM is a truly free alternative. The mapStyle object was the most challenging part to figure out as examples are essentially non-existent. This is how to implement a 3rd party tiling service with react-map-gl:

class Map extends React.Component {

/*...*/

constructor(props) {

/*...*/

this.state = {

/*...*/

viewport: {

width: '100%',

height: 400,

latitude: 43.6532,

longitude: -79.3832,

zoom: 2

}

}

}

render() {

return (

/*...*/

<MapGL

style={this.props.style}

onViewportChange={(viewport) => this.setState({ viewport })}

mapStyle={mapStyle}

{...this.state.viewport}

>

<Draw

/*...*/

/>

</MapGL>

/*...*/

)

}

}

const mapStyle = {

"version": 8,

"name": "OSM Liberty",

"metadata": {

"maputnik:license": "https://github.com/maputnik/osm-liberty/blob/gh-pages/LICENSE.md",

"maputnik:renderer": "mbgljs"

},

"sources": {

"osm a": {

"type": "raster",

"tiles": ["https://a.tile.openstreetmap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png"],

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 19

},

"osm b": {

"type": "raster",

"tiles": ["https://b.tile.openstreetmap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png"],

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 19

},

"osm c": {

"type": "raster",

"tiles": ["https://c.tile.openstreetmap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png"],

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 19

}

},

"layers": [

{ "id": "A osm", "type": "raster", "source": "osm a" },

{ "id": "B osm", "type": "raster", "source": "osm b" },

{ "id": "C osm", "type": "raster", "source": "osm c" }

],

"id": "osm-liberty"

}

Server-side, the fundamental principles are the same as when a user signs up for pickup. The front end sends a post request with the form information and the back end stores this in a database. Things are unique, however, with regards to the password and link_code fields.

Anyone with a sliver of security knowledge should know storing passwords in plain text is an awful idea. It is not only a liability in the event of a hack, it is also a liability in that the service owners can see user passwords at any time. People often re-use passwords which means a malicious party could use BottlesAgainstCOVID.org take control of more important accounts (email, banking, etc.).

The current answer to this is storing salted and hashed passwords.

Hashing is the process of doing complex math equations that cannot be undone. This transforms the password into a seemingly random jumble of characters. The process is, however, not random as the same input will produce the same output every time. An example of an irreversible math operation is XOR.

... but ...

So, given just the result of , it is impossible to work backwards and determine whether both inputs were or .

With bcrypt, this supposedly irreversible process repeats numerous times making it even more resource intensive to try and reverse the hashing operation. Even the most powerful supercomputers would take thousands of years to decrypt a single password.

Salting a password means adding some random chunk of data to the inputted user password. This means that hackers cannot compare stored passwords with known hashes. For example, the bcrypt hash of "hunter2" (no salting) is:

"$2b$10$3I4yPjW4IjTWnLe5IlCELePPPRfchtfn8mBcrLZxJl3rw.j6dpP7u"

A hacker could check for any accounts where the stored password value is this hash and know that user's password without needing to reverse the hash algorithm. Salting adds in some random text so that the hash for "hunter2" becomes something else.

Implementing this with mongoengine and flask_bcrypt libraries looks like this:

# User model declaration

# This is an outline of what the user object looks like in the MongoDB database

# ...

from flask_bcrypt import generate_password_hash # ...

# ...

class User(db.Document): # class User extends db.Document

name = db.StringField(required=True)

email = db.EmailField(required=True, unique=True)

# minimum length of a password is 6 characters

password = db.StringField(required=True, min_length=6)

geo_region = db.PolygonField(required=True)

pickup_times = db.ListField(db.BooleanField(), required=True)

header = db.StringField()

link_code = db.StringField(required=True, unique=True)

drives = db.ListField(db.ReferenceField('PickupInfo', reverse_delete_rule=db.PULL))

# hash_password() is a method of the User class meaning all objects of type "User" can call this method on themselves

def hash_password(self):

self.password = generate_password_hash(self.password).decode('utf8')

# ...

# Flask post request

# This is called when a post request is sent to the "bottlesagainstcovid.org/api/auth/register" endpoint

class RegisterApi(Resource):

def post(self):

try:

body = request.get_json()

user = User(**body.get("details"))

# Passwords are hashed as soon as they are received

user.hash_password()

# ...

Here the hash_password() method does all the salting and hashing work. A secret environment file initialized as part of flask_bcrypt contains the salt. Note that this salt should be a different, randomly generated string for every user.

# in the main app.py flask file

from flask_bcrypt import Bcrypt

# ...

app.config.from_envvar('ENV_FILE_LOCATION')

# ...

bcrypt = Bcrypt(app)

# ...

It is so easy to implement that there's no excuse for storing passwords in plain text. It is also important to note all transfers of data from the front end to the back end are secure through forced use of HTTPS.

The next step is generating the bottle drive operator's unique link_code.

class RegisterApi(Resource):

def post(self):

try:

# ...

user.generate_link_code()

user.save()

session['userId'] = str(user.id)

return redirect("/list")

except FieldDoesNotExist:

raise SchemaValidationError

except NotUniqueError:

raise EmailAlreadyExistsError

except Exception as e:

raise InternalServerError

# generate_link_code() method defined in the User class declaration

# ...

class User(db.Document):

# ...

def generate_link_code(self):

good = "0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ_"

code = ""

for i in range(5):

code += choice(good)

if (enchant.Dict("en_US").check(code) == True):#make sure the code is not an english word

self.generate_link_code()

try:

User.objects.get(link_code = code)#throws an error if no object with the same link_code exits

self.generate_link_code()

except DoesNotExist:

self.link_code = code

# ...

The post request calls the generate_link_code() method. This method randomly picks 5 characters from 63 different URL safe options. It is important that the characters are URL safe to avoid hex values in the URL which make the links ugly. Next, the program checks to make sure the random collection of 5 characters is not a word (to completely avoid any profanity). There is also a check to make sure no other bottle drive operator has the same link_code. However, the chances of this happening are very low.

Calculating the number of possible permutations given a 5-character sample from a 63-character set gives:

Subtracting the number of 5 letter English words (according to this source) gives us:

This means that the odds of a collision occurring, given accounts created is:

This is an extremely small number for any reasonable number of user accounts. Nevertheless, the code is there ... just in case.

Finally, the website rejects any operators already signed up or with too short a password.

Logging in

Login is another feature exclusive to bottle drive operators. The login screen simply sends a post request to the /api/auth/login endpoint and redirects to the page provided by the server. The page shows an error message if the email or password is invalid.

handleLoginSubmit(event) {

/* ... */

var loginData = JSON.stringify({

"email": this.state.email,

"password": this.state.password

})

/* ... */

fetch("/api/auth/login", requestOptions)

.then(response => {

if (response.status === 200) {

window.location.replace(response.url)

} else if (response.status === 401) {

this.setState({ email: "", password: "", unauthorized: true })

}

})

/* ... */

}

The response URL replaces the current URL. This means the /login page is not kept in the browser history. After logging in, the bottle drive operator would have no need to log in again, so this behaviour is intentional.

Furthermore, the login page will redirect automatically to the /list page when logged in. Upon loading the /login page, the front end sends a request to the back end checking if the user is logged in. The server responds with a true or false. This uses the session module in the flask library. Each user receives a cookie upon signing in. Checking for a valid cookie occurs each time the user tries to access a restricted page. The same checking service redirects a logged-out user to the login page.

// Front end request code

// ...

componentDidMount() {

fetch("/api/auth/login")

.then(response => response.json())

.then(result => result && window.location.replace("/list"))

.catch(error => console.log(error))

}

// ...

# Back end response code

class LoginApi(Resource):

# ...

def get(self):

try:

if 'userId' in session:

return jsonify(True)

else:

return jsonify(False)

except Exception as e:

raise InternalServerError

# ...

The server stores the email & salted+hashed password, so authentication happens on the back end. The important part here is the user.check_password() method. This performs the exact same salt+hash operation used when creating the password. Login is successful when this result matches the stored salted+hashed password. This is because only the correct password will ever produce a result matching the stored password. If you are more interested in hashing (or you find this short explanation difficult to understand) check out this video and some of the other videos suggested towards the end.

# Post request

# ...

class LoginApi(Resource):

def post(self):

try:

body = request.get_json()

user = User.objects.get(email=body.get('email'))

authorized = user.check_password(body.get('password'))

if not authorized:

raise UnauthorizedError

session['userId'] = str(user.id)

return redirect("/list")

except (UnauthorizedError, DoesNotExist):

raise UnauthorizedError

except Exception as e:

raise InternalServerError

# ...

# Check password method in the User class

def check_password(self, password):

return check_password_hash(self.password, password)

Adding new bottle drives

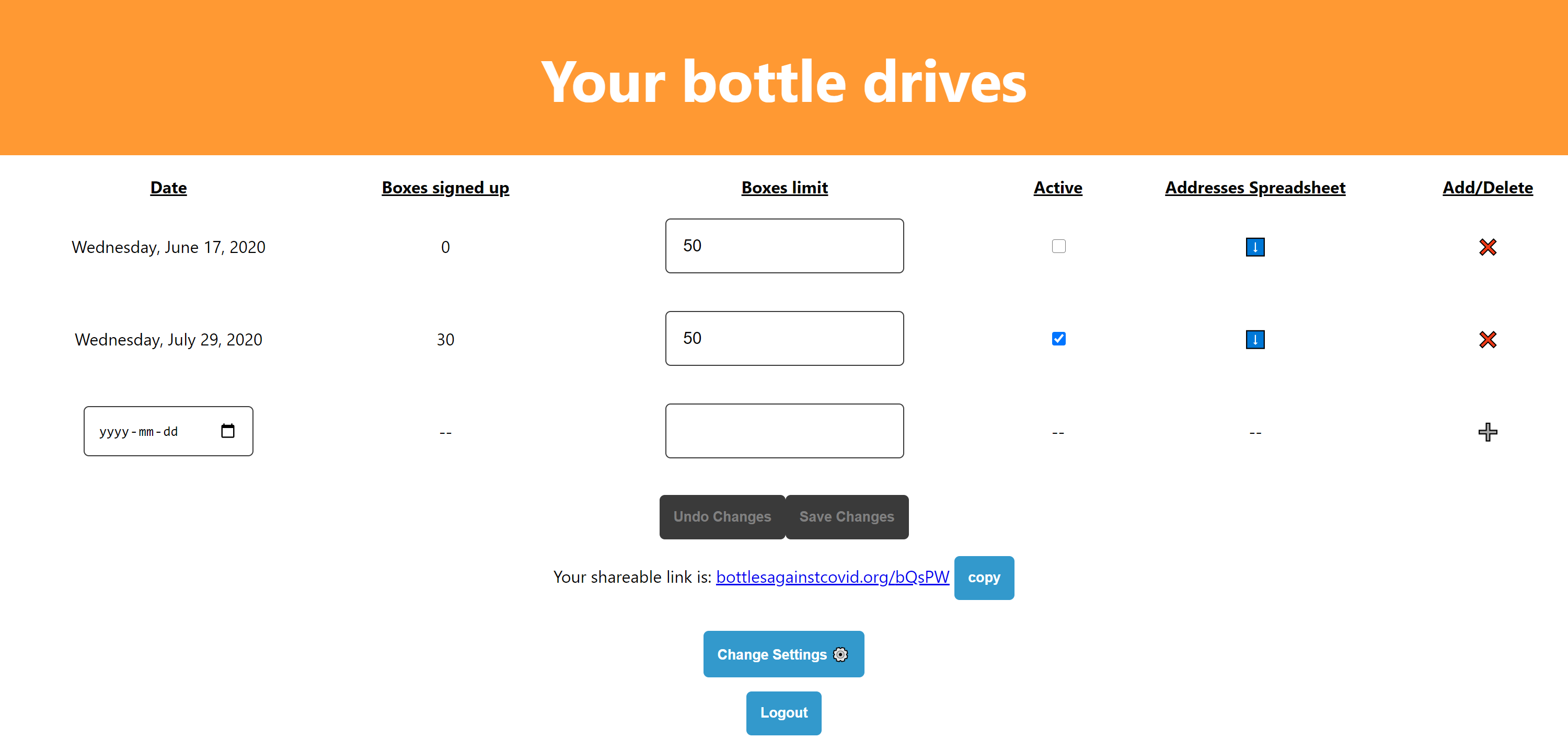

Adding bottle drives happens on the /list page.

To add a bottle drive, the operator simply selects a date, types in a maximum number of boxes, and presses the ➕ button. Filling out these fields automatically updates the state object. Pressing the button sends a post request to the back end with the necessary information. Upon successfully sending the data, the page reloads the table of drives. This makes the new drive visible to the operator.

sendNewDrive() {

/* ... */

const driveData = JSON.stringify({

"date": this.state.newDrive.date,

"crates_limit": this.state.newDrive.crates_limit

})

/* ... */

fetch("/api/list", requestOptions)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(() => {

this.loadDrives()

this.setState({ newDrive: { "date": "", "crates_limit": "" } })

})

/* ... */

}

The back end only creates drives that start tomorrow at the earliest. It rejects any request on a past date or the current date. Also, of note is the addition of the drive object id to the user object. This makes the list of the operator's drives accessible by both searching the link_code and inspecting the specific user object. Inspecting the object takes less time than searching through the entire database of drives. Both paths produce the exact same object; one is not simply a copy of the other. This is also part of a security component where another user cannot delete someone else's drive. Only the creator of a drive can delete it.

# Back end to create a new bottle drive object

class ListDriveApi(Resource):#to modify a bottle drive instance

# ...

def post(self): # make a new drive instance

if 'userId' in session:

try:

user_id = session['userId']

body = request.get_json()

if datetime.strptime(body["date"], "%Y-%m-%d") < datetime.now():

raise ValidationError

user = User.objects.get(id=user_id)

pickupInfo = PickupInfo(**body, created_by=user, active=True, link_code=user.link_code )

pickupInfo.save()

user.update(push__drives=pickupInfo)

user.save()

return "success", 200

# ...

except Exception as e:

# ...

else:

abort(403, "unauthorized")

# ...

The other part of the deletion restriction is registering a delete rule in the MongoDB model declarations.

# ...

User.register_delete_rule(PickupInfo, 'created_by', db.CASCADE)

# ...

Making pickup day easy

Pickup day is extremely easy because the bottle drive operator can download the address and other pickup info of each person registered for a specific bottle drive. All the operator needs to do is click the ⬇️ (download) button next to their bottle drive of choice. This saves a .csv file with each registrant's name, email, address, neighbourhood, number of boxes to pick up, and note. The addition of the neighbourhood field was a suggestion by St. Joe's community campaign officer Kathy Richmond. Listing the neighbourhood makes it easier for operators to know which houses are close to each other and plan the order of pickups accordingly.

Interestingly, the server never stores the .csv file. It instead streams the file to the user. This cuts down on disk use. Streaming works through use of the yield keyword. This allows a function/method (in this case generate()) to return multiple values before halting. Each of these values are then sent to the end user.

import csv

# ...

class DownloadAddressesApi(Resource):

def get(self):

if 'userId' in session:

try:

user_id = session['userId']

date = request.args.get('date', '')

pickupInfo = PickupInfo.objects.get(created_by=user_id, date=date)

def generate(pickupInfo):

data = StringIO()

w = csv.writer(data)

# write header

w.writerow(("Name", "Address", "Neighbourhood", "e-mail", "boxes", "message"))

yield data.getvalue()

data.seek(0)

data.truncate(0)

for item in pickupInfo.addresses:

w.writerow((

item.name,

item.homeAddress,

item.neighbourhood,

item.email,

item.crates,

item.message

))

yield data.getvalue()

data.seek(0)

data.truncate(0)

# stream the response as the data is generated

response = Response(generate(pickupInfo), mimetype='text/csv')

# add a filename

response.headers.set("Content-Disposition", "attachment", filename=f"{pickupInfo.date.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')}-pickup-addresses.csv")

return response

except Exception:

raise InternalServerError

else:

abort(403, "unauthorized")

Reflecting on the build process

React Front end

My experience with React Native at my job last summer and DeltaHacks IV was invaluable for this part. However, I did learn a lot of new things about React and JS from this project.

I think my biggest growth was in design. This is the first website I have made where the visual aspects were considered. All my prior layout experience was with React Native, which is a little bit different from ReactJS. I also feel like I garnered a better understanding of React and JS this time compared to last.

If I were to do this again, I might use something like Preact. I feel as if I have left much of the capabilities of React on the table, and that it may have been overkill.

Also, next time I would use hooks. I have started using hooks on another project and they are significantly easier to use than classes. I am not sure why I was so afraid to use them.

Flask Back End

This part of the build process was almost entirely foreign to me. I had some experience with basic Flask development after my DeltaHacks IV project, but otherwise I was in the dark. I was able to build the foundations for my website thanks to the great tutorials available online, specifically this one, and this one.

If I were to do this part again, I would likely choose a different framework than Flask. I have started another project (it is a secret right now) using FastAPI. I find it much nicer to use than Flask.

MongoDB Database

I will say, using MongoDB with mongoengine was a joy. It was very easy to use and the built-in geo-query capabilities of MongoDB made the search feature on the website's main page a snap.

Writing this blog post

I have not done a blog post like this in a long time. It took an immense amount of time and is likely too long for anyone to read to completion ... but I did catch a lot of fringe mistakes while writing it. Nothing program breaking (as these are easier to notice while writing code), but I found a lot of code that was not needed anymore and made things more complex. It has also helped me reflect on what I learned from this project and where I can improve.